In my last post, I made the seemingly preposterous claim that every business is a media business. Some people agreed, some people disagreed, but the hypothesis definitely caught people’s attention.

So, it might be worth asking, what’s happening with the media companies?

Newspapers, the traditional media companies have been decimated. Revenues have dropped from $67B in 2000 to $20B in 2014.

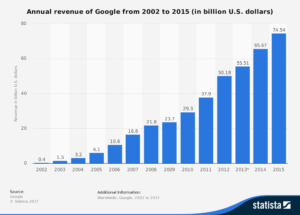

Coincidentally, here are Google’s revenues for a similar time period. It’s not a big mystery where that newspaper revenue is going.

The decline of newspapers in particular, and journalism in general is not exactly news. (Oops, no pun intended.)

But what about Hollywood? Aren’t movies going gangbusters, with sequel after sequel after prequel raking in gobs of cash?

Not so fast.

Movie studios are actually in trouble, losing money and taking on more risk.

See this timely article from Vanity Fair, Why Hollywood as We Know It is Already Over:

Part of the problem, it seems, is that Hollywood still views its interlopers from the north as rivals. In reality, though, Silicon Valley has already won. It’s just that Hollywood hasn’t quite figured it out yet.

…

Netflix is competing not so much with the established Hollywood infrastructure as with its real nemeses: Facebook, Apple, Google (the parent company of YouTube), and others. There was a time not long ago when technology companies appeared to stay in their lanes, so to speak: Apple made computers; Google engineered search; Microsoft focused on office software. It was all genial enough that the C.E.O. of one tech giant could sit on the board of another, as Google’s Eric Schmidt did at Apple.

…

These days, however, all the major tech companies are competing viciously for the same thing: your attention.

…

It all comes back to attention. When the movie studios were at the height of their power, watching “moving pictures” required going to a theater. Now, not only do we have access to hundreds of channels and gazillions of hours of on demand media, we have video games (many of which look just like the movies, and with about the same amount of plot), Facebook (1.8B people) and its cousin networks, Instagram (600 million people) and WhatsApp (over 1B), and other social networks, and endless entertainment in our pockets.

(I could write a whole post about how we need to do a better job of managing the way these apps try to demand our attention, but that’s a different post.)

The point is that blogging, YouTube, social media, and other means of creating and distributing content have made it possible for almost anyone to become a media company. The downside is that when everyone’s a media company, who has time to consume all the media? If everyone’s shouting, who can we hear?

The point of the article is even scarier:

It would be wrong, however, to view this trend as an apocalypse. This is only the beginning of the disruption.

The coming stages involve not needing Aaron Sorkin to write a screenplay, but to have a computer do it. This may sound crazy, but the notion of self-driving cars seemed crazy a decade ago. What’s changing now is not just the power of computer chips themselves, but the way the computers connect to sift through vast amounts of data. Writing software to drive a car is hard, but it’s much easier if all the cars in your fleet essentially have the experience of all the other cars. This kind of processing is coming to the media, too.

When bots create content, the media deluge will become a full on flood, and of course, we will need consumer bots to sift through it. Sound crazy? Some companies already offer services like this for Twitter. (No one really has time to follow 50,000 people.)

What does that mean for your (media) company?

It all goes back to the story.

“The most powerful person in the world is the story teller. The storyteller sets the vision, values and agenda of an entire generation that is to come and Disney has a monopoly on the storyteller business. You know what? I am tired of that bullshit, I am going to be the next storyteller.”

— Steve Jobs

There’s a big difference between the contrived B.S. that passes for most corporate communication– whether it’s an internal status report, a website, a marketing document, or a proposal– and an actual story.

People don’t change because of logic. They change because they see themselves in a different story.